Tooling Around: Letting Agents Do Stuff is Hard

There is a messy reality of giving AI agents tools to work with. This is particularly true given that the Model Control Protocol (MCP) has become the default way to connect AI models to external tools. This has happened faster than anyone expected, and faster than the security aspects could keep up.

This article is about what’s actually involved in deploying MCP servers safely. Not the general philosophy of agent security, but the specific problems you hit when you give Claude or ChatGPT access to your filesystem, your APIs, your databases. It covers sandboxing options, policy approaches, and the trade-offs each entails.

If you’re evaluating MCP tooling or building infrastructure for tool-using agents, this should help you better understand what you’re getting into.

Side note: MCP isn't the only game in town; OpenAI has native function calling, Anthropic has a tool-use API, and LangChain has tool abstractions. So yes, there are other approaches to tool integration, but MCP has become dominant enough that its security properties matter for the ecosystem as a whole.

How MCP became the default (and why that’s currently problematic)

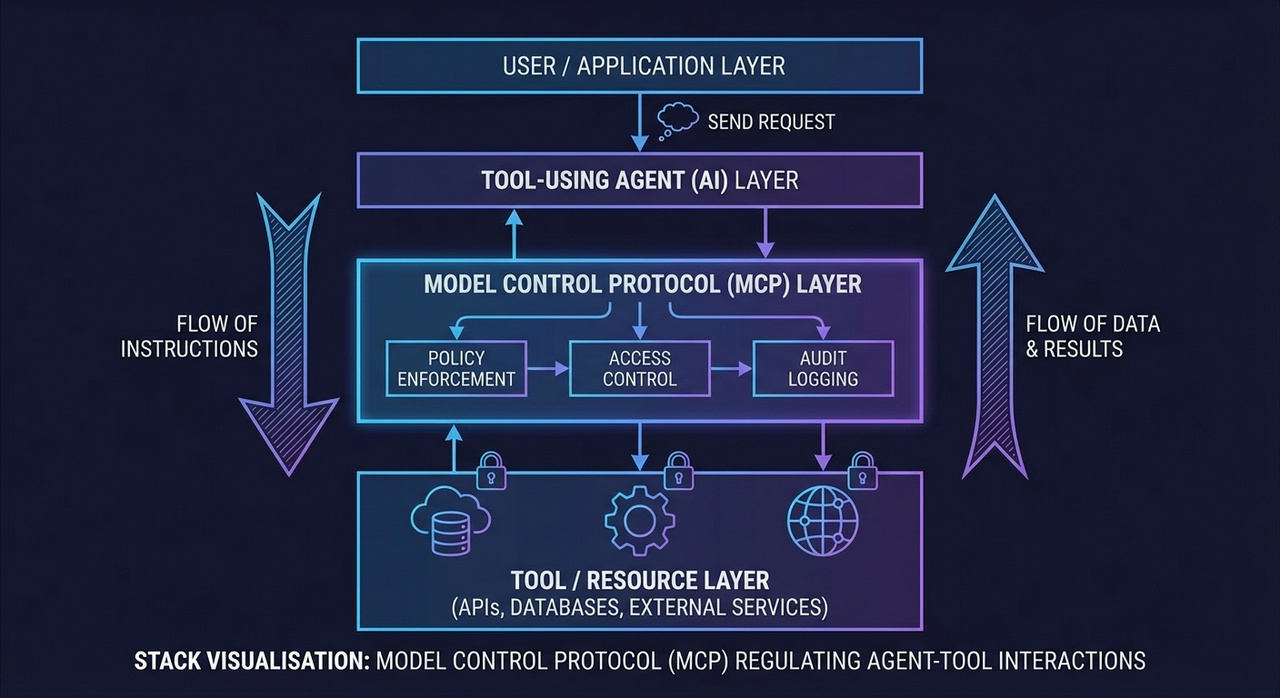

The Model Context Protocol defines a client-server architecture for connecting AI models to external resources. The model makes requests via an MCP client. MCP servers handle the actual interaction with filesystems, databases, APIs, and whatever else. It’s a standardised way to say “I need to read this file” and have something actually do it.

MCP wasn’t designed to be enterprise infrastructure. Anthropic released it in November 2024 as a modest open specification. Then it kind of just exploded.

As Simon Willison observed in his year-end review, “MCP’s release coincided with the models finally getting good and reliable at tool-calling, to the point that a lot of people appear to have confused MCP support as a pre-requisite for a model to use tools.” By May 2025, OpenAI, Anthropic, and Mistral had all shipped API-level support within eight days of each other.

This rapid adoption created a problem. MCP specifies communication mechanisms but doesn’t enforce authentication, authorisation, or access control. Security was an afterthought. Authentication was entirely absent from the early spec; OAuth support only landed in March 2025. Research on the MCP ecosystem found more than 1,800 MCP servers on the public internet without authentication enabled.

Security researcher Elena Cross put it amusingly and memorably: “the S in MCP stands for security.” Her analysis outlined attack vectors, including tool poisoning, silent redefinition of tools after installation, and cross-server shadowing, in which a malicious server intercepts calls intended for a trusted server.

The MCP spec does say “there SHOULD always be a human in the loop with the ability to deny tool invocations.” But as Willison points out, that SHOULD needs to be a MUST. In practice, it rarely is.

The breaches so far

These theoretical vulnerabilities have already been exploited. A timeline of MCP incidents in 2025:

- Asana’s MCP implementation had a logic flaw allowing cross-tenant data access

- Anthropic’s own MCP Inspector tool allowed unauthenticated remote code execution—a debugging tool that could become a remote shell

- The mcp-remote package (437,000+ downloads) was vulnerable to remote code execution

- A malicious “Postmark MCP Server” (1,500 weekly downloads) was modified to silently BCC all emails to an attacker

- Microsoft 365 Copilot was vulnerable to hidden prompts that exfiltrated sensitive data.

These aren’t sophisticated attacks; they’re basic security failures, such as command injection, missing auth, supply chain compromise, applied to a context where consequences are amplified by what the tools can do.

The normalisation problem

What concerns me most isn’t any specific vulnerability. It’s the cultural dynamic emerging around MCP deployment.

Johann Rehberger has written about “the Normalisation of Deviance in AI”—a concept from sociologist Diane Vaughan’s analysis of the Challenger disaster.

The core insight: organisations that repeatedly get away with ignoring safety protocols bake that attitude into their culture. It works fine… until it doesn’t. NASA knew about the O-ring problem for years. Successful launches made them stop taking it seriously.

Rehberger argues the same pattern is playing out with AI agents:

“In the world of AI, we observe companies treating probabilistic, non-deterministic, and sometimes adversarial model outputs as if they were reliable, predictable, and safe.”

Willison has been blunter. In a recent podcast:

“I think we’re due a Challenger disaster with respect to coding agent security. I think so many people, myself included, are running these coding agents practically as root, right? We’re letting them do all of this stuff.”

That “myself included” is telling. Even people who understand the risks are taking shortcuts because the friction of doing it properly is high, and nothing bad has happened yet. That’s exactly how normalisation of deviance works.

Sandboxing: your options

So, how do you actually deploy MCP servers with some safety margin? The most direct approach is isolation. Run servers in environments where even if they’re compromised, damage is contained (the “blast radius”).

Standard containers

This is basic isolation, but with containers sharing the host kernel. A container escape vulnerability, therefore, gives an attacker full host access, and container escapes do occur. For code you’ve written and audited, containers are probably fine. For anything else, they’re not enough.

gVisor

gVisor implements a user-space kernel that intercepts system calls. The MCP server thinks it’s talking to Linux, but it’s talking to gVisor, which decides what to allow. Even kernel vulnerabilities don’t directly compromise the host.

The tradeoff is compatibility. gVisor implements about 70-80% of Linux syscalls. Applications that need exotic kernel features, such as advanced ioctls or eBPF, won’t work. For most MCP server workloads, this doesn’t matter. But you’ll need to test.

Firecracker

Firecracker, built by AWS for Lambda and Fargate, is the strongest commonly-available isolation. It offers full VM separation optimised for container-like speed. A Firecracker microVM runs its own kernel, completely separate from the host. So there is no shared kernel to exploit. The attack surface shrinks to the hypervisor, a much smaller codebase than a full OS kernel.

Startup times are reasonable (100-200ms), and resource overhead is minimal. Firecracker achieves this by being ruthlessly minimal. No USB, no graphics, no unnecessary virtual devices.

For executing untrusted or AI-generated code, Firecracker is currently the gold standard. The tradeoff is operational complexity. You need KVM support (bare-metal or nested virtualisation), different tooling than for container deployments, and more careful resource management.

Mixing levels

Many production setups use multiple isolation levels. Trusted infrastructure in standard containers. Third-party MCP servers under gVisor. Code execution sandboxes in Firecracker, with isolation directly aligned to the threat level.

The manifest approach

Sandboxing handles what happens when things go wrong. Manifests try to prevent things from going wrong by declaring what each component should do.

Each MCP server ships with a manifest that describes the required permissions. This includes filesystem paths, network hosts, and environment variables. At runtime, a policy engine reads the manifest, gets user consent, and configures the sandbox to enforce exactly those permissions. Nothing more.

The AgentBox project works this way. A manifest might declare read access to /project/src, write access to /project/output, and network access to api.github.com. The sandbox gets configured with exactly that. If the server tries to read /etc/passwd or connect to malicious.org, the request fails, not because a gateway blocked it, but because the capability doesn’t exist.

There are real advantages to this approach. Users see what each component requires before granting access. Suspicious permission requests stand out. The same server deploys across environments with consistent security properties.

Unfortunately, the problems are also real. Manifests can only restrict permissions they know about, so side channels and timing attacks may not be covered. Filesystem and network permissions are coarse.

A server that legitimately needs api.github.com might abuse that access in ways the manifest can’t prevent. And who creates the manifests? Who audits them? Still, explicit, auditable permission declarations beat implicit unlimited access, even if they’re imperfect.

Beyond action logs: execution decisions

This is something I think gets missed in most MCP observability discussions. Logging “Claude created x.ts” is useful, but the harder problems show up when you ask:

- Why was this action allowed at this point in the workflow?

- What state was assumed when it ran?

- Was this a retry, a branch, or a first-time execution?

Teams get stuck when agent actions are logged after the fact, but aren’t tied to a durable execution state or policy context. You get perfect traces of what happened with no ability to answer why it was allowed to happen.

Current observability tooling (LangSmith, Arize, Langfuse, etc.) focus on the “what happened” side. Every step traced, every tool call logged, every prompt inspectable. This is useful for debugging and cost tracking, but it doesn’t answer the security question “given the policy context at this moment, should this action have been permitted?”

A better pattern treats each agent step as an explicit execution unit:

- Pre-conditions: permissions, budgets, invariants that must hold before execution

- A recorded decision: allowed/blocked/deferred, with the policy context behind it

- Post-conditions and side effects: what changed

Your logs then answer not just what happened, but why it was allowed. When something goes wrong, you trace through the decision chain and see where policy should have intervened but didn’t.

This is harder than after-the-fact logging. It means integrating policy evaluation into the execution path rather than bolting observability on separately. But without it, you’re likely to end up doing forensics on incidents instead of preventing them.

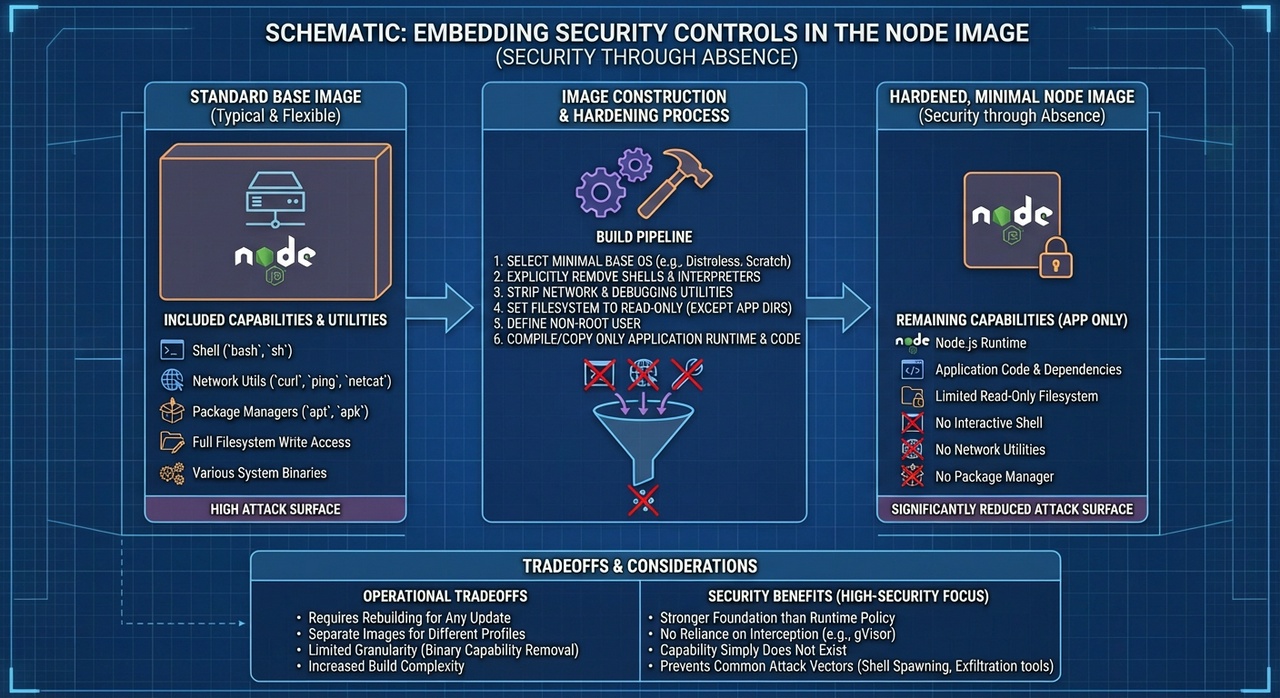

Embedding controls in the Node Image

A more aggressive approach is to embed security controls directly into base images. Rather than a runtime policy, you construct images where certain capabilities don’t exist.

This is security through absence. An image without a shell can’t spawn a shell. Without network utilities, no data exfiltration can happen over the network. Without write access to certain paths, those paths can’t be modified, not because policy blocks the write, but because the filesystem capability isn’t there at all.

The appeal is that you’re not trusting a policy layer. You’re not hoping gVisor correctly intercepts the dangerous syscall. The capability simply doesn’t exist at the image level.

The tradeoffs (there are always tradeoffs!) are mostly operational. You’ll need separate base images for each security profile. Updates mean rebuilding, not reconfiguring. Granularity is limited, as you can remove broad capability categories but can’t easily express “network access only to api.github.com.”

For high-security deployments where operational complexity is acceptable, this approach provides a stronger foundation than runtime enforcement alone. For most teams, it’s probably overkill, but worth knowing about.

Framework-level options

Several frameworks are emerging to standardise MCP security patterns.

SAFE-MCP (Linux Foundation / OpenID Foundation backed) defines patterns for secure MCP deployment, grounded in common failure modes where identity, intent, and execution are distributed across clients, servers, and tools.

The AgentBox approach targets MCP servers as the enforcement point, i.e., the least common denominator across agentic AI ecosystems. Securing MCP servers protects the interaction surface and shifts enforcement closer to the system layer.

For credentials specifically, the Astrix MCP Secret Wrapper wraps any MCP server to pull secrets from a vault at runtime. So no secrets are exposed on host machines, and the server gets short-lived, scoped tokens instead of long-lived credentials.

None of these solves the fundamental problems. But they encode collective learning about what goes wrong and are worth understanding, even if you don’t need to adopt them wholesale.

Where this leaves us

MCP security in 2026 is a mess of emerging standards, competing approaches, and incidents that keep teaching us things we should have anticipated.

It’s like that box of Lego that mixes several original sets whose instructions are long gone. We have the pieces, and we sort of know what we want to build should look like, but we’re just dipping into the jumbled box to piece it together.

If I had to summarise:

Sandboxing works but costs something. gVisor and Firecracker provide real isolation. They also add operational weight. Match the isolation level to the actual threat.

Manifests help, but aren’t complete. Explicit permission declarations make the attack surface visible. They don’t prevent all attacks.

Observability needs policy context. Logging what happened isn’t enough. You need to know why it was allowed.

We’re probably going to learn some hard lessons. Too many teams are running MCP servers with excessive permissions, inadequate monitoring, and Hail Mary hopes that nothing goes wrong.

Organisations that figure this out will be able to give their agents more capability, because they can actually trust them with it. Everyone else will either hamstring their agents to the point of uselessness or find out the hard way what happens when highly capable tools meet insufficient or non-existent constraints.

References

- Simon Willison, “2025: The year in LLMs”

- Simon Willison, “Model Context Protocol has prompt injection security problems”

- Simon Willison, “LLM predictions for 2026”

- Johann Rehberger, “The Normalization of Deviance in AI”

- Elena Cross, “The S in MCP Stands for Security”

- AuthZed, “A Timeline of Model Context Protocol Security Breaches”

- Astrix Security, “State of MCP Server Security 2025”

- The New Stack, “SAFE-MCP: A Community-Built Framework for AI Agent Security”

- AgentBox, “Securing AI Agent Execution”

- gVisor, “Security Model”

- AgentSphere, “Choosing a Workspace for AI Agents”

I am a partner in Better than Good. We help companies make sense of technology and build lasting improvements to their operations. Talk to us today: https://betterthangood.xyz/#contact