Meta’s GEM: What the largest ads foundation model means for your marketing

Meta has been quietly building something significant. Most marketers haven’t fully grasped the importance because it has been wrapped in machine learning jargon and engineering blog posts.

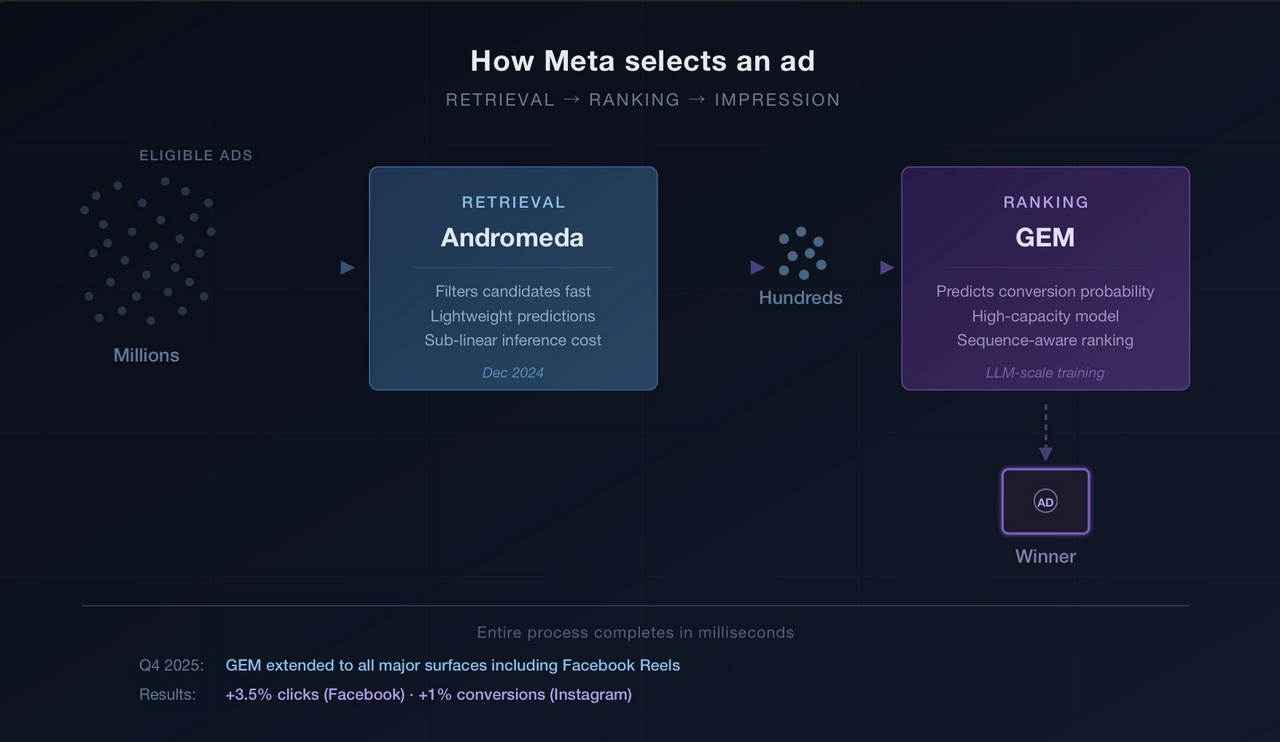

The Generative Ads Recommendation Model, which Meta calls GEM, is the largest foundation model ever built specifically for advertising recommendation. It’s live across every major surface on Facebook and Instagram, and the Q4 2025 numbers, a 3.5% increase in clicks on Facebook, more than 1% lift in conversions on Instagram, are worth paying attention to at Meta’s scale.

Eric Seufert recently published a deep technical breakdown of GEM drawing on Meta’s own whitepapers, a podcast interview with Meta’s VP of Monetization Infrastructure Matt Steiner, and the company’s earnings calls. His analysis is the most detailed public account of how these systems actually work, and what follows draws heavily on it. I’d recommend reading his piece in full, because Meta has been deliberately vague about the internals, and Seufert has done the work of triangulating across sparse sources to build a coherent picture.

That sparseness is worth mentioning upfront. Meta has strong commercial reasons to keep the details thin. What we’re working with is a combination of carefully worded whitepapers, earnings call quotes from executives who are choosing their words, and one arXiv paper that may or may not describe GEM’s actual production architecture. I think the picture that emerges is convincing. But we should be honest about the fact that we’re reading between lines Meta drew deliberately.

The retrieval/ranking split

If you’re going to understand what GEM changes, you need to grasp the two-stage model Meta uses to select ads. Seufert explains this well: first ad retrieval, then ad ranking. These are different problems with different systems and different computational constraints.

Retrieval is Andromeda’s job (publicly named December 2024). It takes the vast pool of ads you could theoretically see (potentially millions) and filters to a shortlist of tens or hundreds. This has to be fast and cheap, so the model runs lighter predictions on each candidate. Think of it as triage.

Ranking is where GEM operates. It takes that shortlist and predicts which ad is most likely to produce a commercial result: a click, a purchase, a signup. The ranking model is higher-capacity but processes far fewer candidates, and the whole thing has to complete in milliseconds. Retrieval casts the net; ranking picks the fish.

When Meta reports GEM performance gains, they’re talking about this second stage getting more precise. The system isn’t finding more potential customers, it’s getting better at predicting which ad, shown to which person, at which moment, will convert.

The retrieval/ranking distinction is coveted in more depth in Bidding-Aware Retrieval, a paper by Alibaba researchers that attempts to align the often upper-funnel predictions made during retrieval with the lower-funnel orientation of ranking while accommodating different bidding strategies.

Sequence learning: why this architecture is different

Here’s where it gets interesting, and where I think the implications for how you run campaigns start to bite.

Previous ranking models used what Meta internally calls “legacy human-engineered sparse features.” An analyst would decide which signals mattered, past ad interactions, page visits, demographic attributes. They’d aggregate them into feature vectors and feed them to the model. Meta’s own sequence learning paper admits this approach loses sequential information and leans too heavily on human intuition about what matters.

GEM replaces that with event sequence learning. Instead of pre-digested feature sets, it ingests raw sequences of user events and learns from their ordering and combination. Meta’s VP of Monetization Infrastructure put it this way: the model moves beyond independent probability estimates toward understanding conversion journeys. You’ve browsed cycling gear, clicked on gardening shears, looked at toddler toys. Those three events in that sequence change the prediction about what you’ll buy next.

The analogy Meta keeps reaching for is language models predicting the next word in a sentence, except here the “sentence” is your behavioural history and the “next word” is your next commercial action. People who book a hotel in Hawaii tend to convert on sunglasses, swimsuits, snorkel gear. The sequence is the signal. Individual events, stripped of their ordering, lose most of that information.

This matters because it means GEM sees your potential customers at a resolution previous systems couldn’t reach. It’s predicting based on where someone sits in a behavioural trajectory, not just who they are demographically or what they clicked last Tuesday. For products that fit within recognisable purchase journeys, this should translate directly into better conversion prediction and fewer wasted impressions.

But I want to highlight something Seufert’s analysis makes clear: we don’t know exactly how granular these sequences are in practice, or how long the histories GEM actually ingests at serving time. The GEM whitepaper says “up to thousands of events,” but there’s a meaningful gap between what a model can process in training and what it processes under millisecond latency constraints in production.

How they solve the latency problem

This is the engineering puzzle at the centre of the whole thing. Rich behavioural histories make better predictions, but you can’t crunch thousands of events in the milliseconds available before an ad slot needs filling.

Seufert’s analysis draws on a Meta paper describing LLaTTE (LLM-Style Latent Transformers for Temporal Events) that appears to address exactly this tension, though Meta hasn’t confirmed it’s the architecture powering GEM in production.

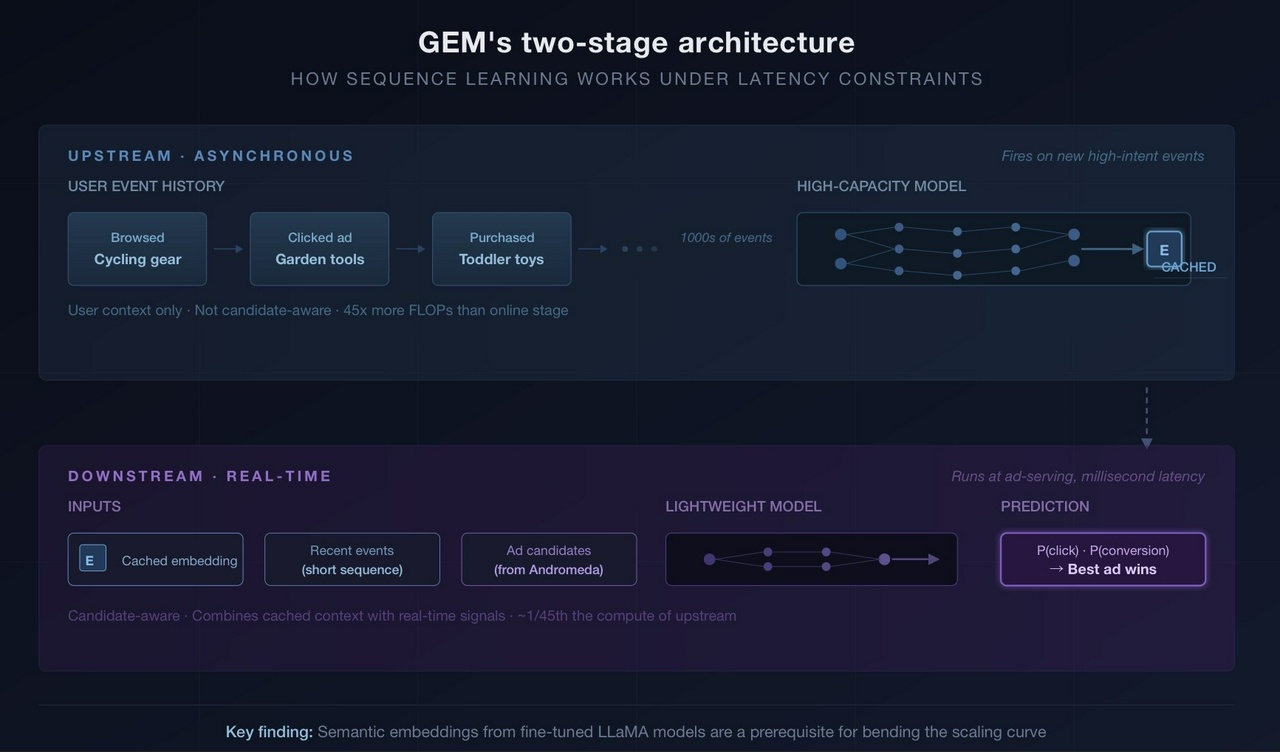

The solution is a two-stage split. A heavy upstream model runs asynchronously whenever new high-intent events arrive (like a conversion). It processes the user’s extended event history, potentially thousands of events, and caches the result as an embedding. This model doesn’t know anything about specific ad candidates. It’s building a compressed representation of who this user is and what their behavioural trajectory looks like.

Then a lightweight downstream model runs in real time at ad-serving. It combines that cached user embedding with short recent event sequences and the actual ad candidates under consideration. The upstream model consumes more than 45x the sequence FLOPs of the online model. That asymmetry is the whole trick, you amortise the expensive computation across time, then make the cheap real-time decision against a rich precomputed context.

One detail from Seufert’s breakdown that I keep coming back to: the LLaTTE paper found that including content embeddings from fine-tuned LLaMA models, semantic representations of each event, was a prerequisite for “bending the scaling curve.” Without those embeddings, throwing more compute and longer sequences at the model doesn’t produce predictable gains. With them, it does. That’s a specific and testable claim about what makes the architecture work, and it’s one of the few pieces of genuine technical disclosure in the public record.

The scaling law question

This is where I think the commercial story gets properly interesting, and also where I’d encourage some healthy scepticism.

Meta’s GEM whitepaper and the LLaTTE paper both reference Wukong, a separate Meta paper attempting to establish a scaling law for recommendation systems analogous to what we’ve observed in LLMs. In language models, there’s a predictable relationship between compute invested and capability gained. More resources reliably produce better results. If the same holds for ad recommendation, then GEM’s current performance is early on a curve with a lot of headroom.

Meta’s leadership is betting heavily that it does hold. On their most recent earnings call, they said they doubled the GPU cluster used to train GEM in Q4. The 2026 plan is to scale to an even larger cluster, increase model complexity, expand training data, deploy new sequence learning architectures. The specific quote that should get your attention is “This is the first time we have found a recommendation model architecture that can scale with similar efficiency as LLMs.”

The whitepaper claims a 23x increase in effective training FLOPs. The CFO described GEM as twice as efficient at converting compute into ad performance compared to previous ranking models.

Now, the sceptic’s reading. Meta is a company that spent $46 billion on capex in 2024 and needs to justify continued spending at that pace. Claiming their ad recommendation models follow LLM-like scaling laws is convenient because it turns massive GPU expenditure into a story about predictable returns. I’m not saying the claim is wrong, the Q4 numbers suggest something real is happening, but we should notice that this is also the story Meta needs to tell investors right now. The performance numbers are self-reported and the scaling claims are mostly untestable from outside.

That said, the quarter-over-quarter pattern is hard to dismiss. Meta first highlighted GEM, Lattice, and Andromeda together in a March 2025 blog post, and Seufert describes the cumulative effect of all three as a “consistent drumbeat of 5-10% performance improvements” across multiple quarters. No single quarter looks revolutionary, but they compound. And the extension of GEM to all major surfaces (including Facebook Reels in Q4) means those gains now apply everywhere you’re buying Meta inventory, not just on selected placements.

The creative volume angle

There’s a second dimension here that connects to where ad production is heading. Meta’s CFO explicitly linked GEM’s architecture to the expected explosion in creative volume as generative AI tools produce more ad variants. The system’s efficiency at handling large data volumes will be “beneficial in handling the expected growth in ad creative.”

This is the convergence I think experienced marketers should be watching most closely. More creative variants per advertiser means more candidates per impression for the ranking system to evaluate. An architecture that gets more efficient with scale, rather than choking on it, turns higher creative volume from a cost problem into a performance advantage. Seufert explores this theme further in The creative flood and the ad testing trap.

If you’re producing five ad variants today, producing fifty becomes a different proposition when the ranking system can actually learn from and differentiate between those variants at speed. The advertisers who benefit most from GEM’s improvements will be those feeding it more creative options, not those running the same three assets on rotation.

What this means for how you spend

I’m not going to pretend these architectural details should change your Monday morning. But a few things follow from them that are worth sitting with.

GEM’s purpose is to outperform human intuition at predicting conversions from behavioural sequences. If you’re still running heavy audience targeting with rigid constraints, you’re limiting the data the system can learn from. Broad targeting with strong creative has been the winning approach on Meta for a while. GEM widens that gap.

The bottleneck is shifting from targeting precision to creative supply. As the ranking model gets better at matching specific creative to specific users in specific behavioural moments, the constraint becomes whether you’re giving it enough material to work with.

Your measurement windows probably also need revisiting. If GEM is learning from extended behavioural sequences, attribution models that only look at last-touch or short windows will undercount Meta’s contribution to conversions that unfold over days or weeks.

And watch the earnings calls. The 2026 roadmap (larger training clusters, expanded data, new sequence architectures, improved knowledge distillation to runtime models) suggests we’re in the early phase. If the scaling law holds (and that’s a real if, not a rhetorical one), the gap between platforms running this kind of architecture and those that aren’t will widen.

Meta is rebuilding its ad infrastructure around a small number of very large foundation models, GEM, Andromeda, and Lattice, that learn from behavioural sequences rather than hand-picked features.

The results so far are impressive. Whether the scaling story plays out as cleanly as Meta’s investor narrative suggests is genuinely uncertain. But for marketers running at scale on Meta, the platform is getting measurably better at the thing you’re paying it to do, and the trajectory of improvement appears to have more room than previous architectures allowed.

I am a partner in Better than Good. We help companies make sense of technology and build lasting improvements to their operations. Talk to us today: https://betterthangood.xyz/#contact