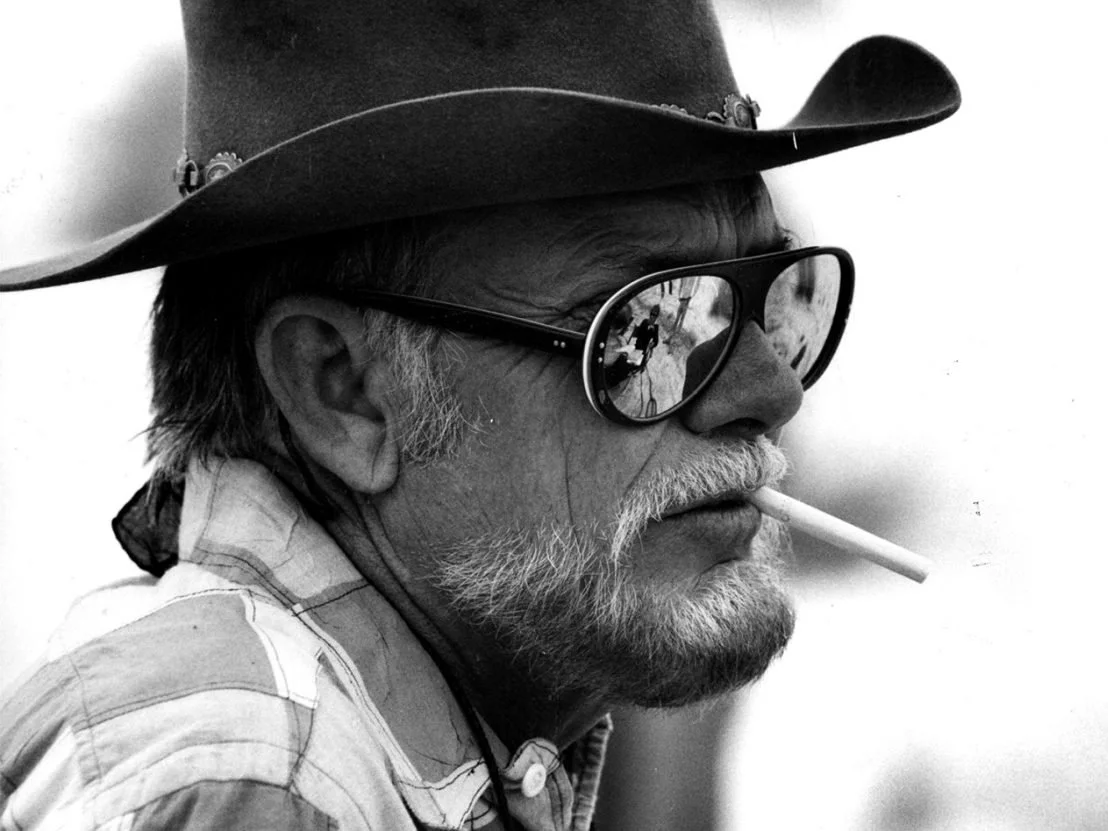

Favourite Directors: Sam Peckinpah

Sam Peckinpah (1925-84) directed 14 pictures in 22 years, nearly half of them compromised by lack of authorial control due to studio interference. The Deadly Companions (1961), Major Dundee (1965), The Wild Bunch (1969), Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973), Convoy (1978) and The Osterman Weekend (1983) were all taken off him in post-production and released to the public in what the director considered a corrupted form.

The Wild Bunch was pulled from its initial release and re-edited by Warner Bros, with no input from the director. Even his first great success, Ride the High Country (1962), saw him booted out of the editing suite, though it was in the very latter stages of post, with no serious damage done.

An innovative filmmaker enamoured with the myths of the old west, if Peckinpah was (as Wild Bunch producer Phil Feldman believed) a directorial genius, he was also a worryingly improvisational one. Along with his extraordinary use of slow motion, freeze-frame and rapid montage, he liked to shoot with up to seven cameras rolling, very rarely storyboarded and went through hundreds of thousands of feet of celluloid (just one of the reasons he alarmed and irked money-conscious studio bosses).

His intuitive method of movie-making went against the grain of studio wisdom and convention. Peckinpah was like a prospector panning for gold. The script was a map, the camera a spade, the shoot involved the laborious process of mining material, and the editing phase was where he aimed to craft jewels.

The Wild Bunch

Set in 1913 during the Mexican revolution, The Wild Bunch sees a band of rattlesnake-mean old bank robbers, led by William Holden’s Pike Bishop, pursued across the US border by bounty hunters into Mexico, a country and landscape that in Peckinpah’s fiery imagination is less a location and more a state of mind.

It’s clear America has changed, and the outlaw’s way of living is nearly obsolete. “We’ve got to start thinking beyond our guns, those days are closing fast,” Bishop informs his crew, a line pitched somewhere between rueful reality check and lament.

The film earned widespread notoriety for its “ballet of death” shootout, where bullets exploded bodies into fireworks of blood and flesh. Peckinpah wanted the audience to taste the violence, smell the gunpowder, be provoked into disgust, while questioning their desire for violent spectacle. 10,000 squibs were rigged and fired off for this kamikaze climax, a riot of slow-mo, rapid movement, agonised, dying faces in close-ups, whip pans and crash zooms on glorious death throes, and a cacophony of ear-piercing noise from gunfire and yelling.

Steve McQueen

His first teaming with Steve McQueen in Junior Bonner (1972) is well worth checking out, even though it’s missing the trademark Peckinpah violence. The story of a lonely rodeo rider reuniting with his family is an ode to blue-collar living, a soulful and poetic work proving that SP could do so much more than mere blood-and-guts thrills.

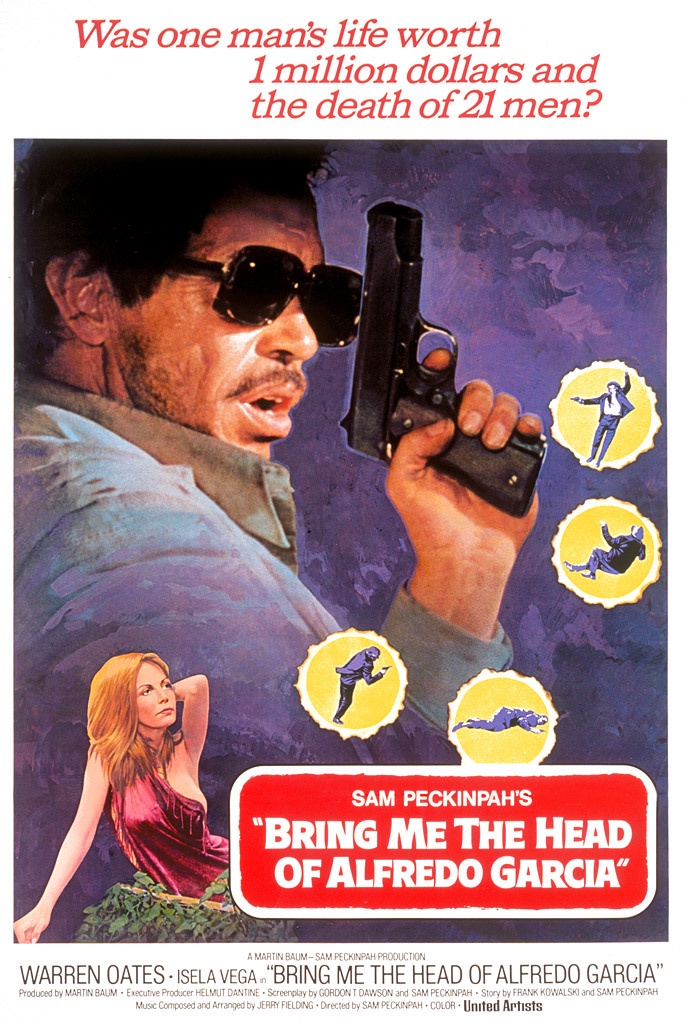

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia

A nightmarish south-of-the-border gothic tale in which a dive-bar piano player (Warren Oates), sensing a scheme to strike it rich, sets off to retrieve the head of a man who got a gangster’s teenage daughter pregnant. It’s the savage cinema of Peckinpah in its purest form: part love story, part road movie, part journey into the heart of darkness – and all demented.

As with his final masterwork, Cross of Iron (1977), a war movie told from the German side, these films can appear alarmingly nihilistic, or as if they’re wallowing in sordidness. But while Peckinpah’s films routinely exhibit deliberately contradictory thinking and positions, he was a profoundly moral filmmaker. The “nihilist” accusation doesn’t wash. What we see in his work is more a bitterness toward human nature’s urge to self-destruction.

I am a partner in Better than Good. We help companies make sense of technology and build lasting improvements to their operations. Talk to us today: https://betterthangood.xyz/#contact