AI Slop: Psychology, History, and the Problem of the Ersatz

In 2025, the term “slop” emerged as the dominant descriptor for low-quality AI-generated output. It has quickly joined our shared lexicon, and Merriam-Webster's human editors chose it as their Word of the Year.

As a techno-optimist, I am at worst ambivalent about AI outputs, so I struggled to understand the various furores that have erupted about its use. Shrimp Jesus seemed harmless enough to me.

To start with, the word itself reveals something important about the nature of human objection. Slop suggests something unappetising and mass-produced, feed rather than food, something that fills space without nourishing. The visceral quality of negative reaction, the almost physical disgust many people report when encountering AI-generated outputs, suggests that something more profound than aesthetic preference is at play.

To understand why AI output provokes such strong reactions, we need to examine the psychological mechanisms that govern how humans relate to authenticity, creativity, and the products of other minds, while also placing this moment in historical context alongside other periods of technological upheaval that generated similarly intense resistance.

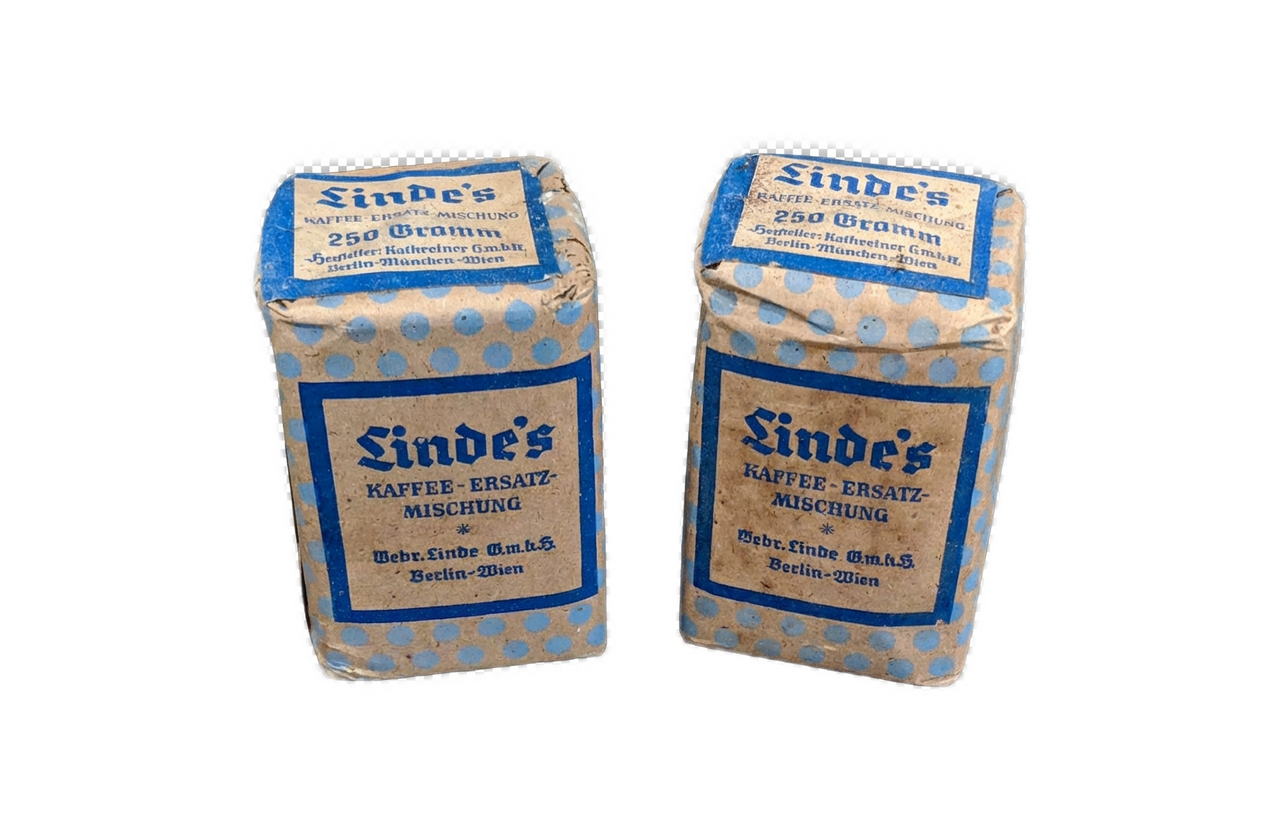

The German word ersatz offers a helpful frame for understanding what is at stake. The term entered widespread English usage during the World Wars, when Germany, facing material shortages due to blockades, produced ersatz versions of scarce commodities. Ersatz coffee made from roasted acorns or chicory, ersatz rubber from synthetic compounds, and ersatz bread bulked out with sawdust or potato flour.

These substitutes might have performed the basic function of the original; you could drink the liquid, and it was warm and brown, but everyone understood they were not the real thing. The word carries a particular connotation that distinguishes it from “fake” or “counterfeit,” which imply deliberate deception. Ersatz instead suggests something that occupies the space of the genuine article while being fundamentally hollow. A substitute that reminds you of what you are missing even as it attempts to fill the gap.

AI-generated output is the ultimate ersatz. It presents the surface features of human creative output, the structure, the vocabulary, and the apparent reasoning, while lacking the underlying consciousness, experience, and intention that give authentic work its meaning. The discomfort people report when encountering AI output often has the quality of encountering the ersatz: to the unwary, the sharp offence of being deceived, but to most, the broader revulsion of receiving a substitute when one expects the genuine article. Understanding this ersatz quality and why it provokes such strong reactions requires us to draw on multiple frameworks from psychology, philosophy, and history.

The Psychology of Authenticity and the Ersatz

Categorical Ambiguity and Cognitive Discomfort

One of the most robust findings in cognitive psychology concerns how humans process information that defies easy categorisation. The anthropologist Mary Douglas, in her seminal work “Purity and Danger,” demonstrated that objects and phenomena which transgress categorical boundaries reliably provoke disgust and anxiety across cultures.

AI-generated output occupies precisely this kind of liminal space; it presents the surface characteristics of human creative output without the underlying process that gives such output its meaning. A poem appears to be a poem, with meter, metaphor, and emotional resonance, yet it emerged from statistical pattern matching rather than lived experience. It is ersatz poetry, occupying the category while lacking the essential substance.

This categorical anomaly creates what psychologists call “processing disfluency,” a sense that something is wrong even when we cannot immediately articulate what. The brain's pattern-recognition systems detect subtle inconsistencies, whether in the too-smooth quality of AI prose, the slightly uncanny composition of AI images, or the hollow centre of AI-generated arguments that proceed through the motions of reasoning without genuine understanding. This detection often happens below the threshold of conscious awareness, manifesting as unease or irritation before it becomes explicit recognition. We sense we are drinking chicory coffee before we can name what is missing.

The Uncanny Valley Expanded

Masahiro Mori's concept of the uncanny valley, originally developed to describe human responses to humanoid robots, provides a useful framework for understanding reactions to AI output more broadly. Mori observed that as artificial entities become more human-like, our affinity for them increases until a critical point where near-perfect resemblance suddenly triggers revulsion. The problem is not that the entity is clearly artificial but that it is almost indistinguishable from the genuine article while remaining fundamentally different in some hard-to-specify way.

AI-generated output has entered its own uncanny valley. Early chatbots and obviously computer-generated images posed no psychological threat because their artificiality was immediately apparent. Contemporary AI systems produce outputs that can fool casual observation while still betraying their origins to closer scrutiny. This creates an increased cognitive burden as consumers of output must now actively evaluate whether what they are reading or viewing originated from a human mind. This task was previously unnecessary and introduces new friction into basic information processing.

Terror Management and Existential Threat

Terror Management Theory, developed by Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, and Tom Pyszczynski, proposes that much human behaviour is motivated by the need to manage anxiety about mortality. Humans cope with awareness of death by investing in cultural worldviews that provide meaning and by pursuing self-esteem through valued social roles. AI represents a peculiar kind of existential threat because it challenges the specialness and irreplaceability of human cognition.

These very capacities have traditionally distinguished us from the rest of nature and provided a foundation for meaning-making. So when a machine can produce decent poetry, generate persuasive arguments, or create images that move viewers emotionally, the uniqueness of human consciousness becomes less clear. This is not only an economic threat, although it is certainly that too, but also an ontological one.

If the products of human creativity can be copied by systems that lack an inner life, suffering, joy, and personal investment in their output, then what exactly is the value of human consciousness? The imitation not only risks replacing the genuine but also questions whether the distinction even matters. The visceral rejection of AI output can partly be seen as a defensive response to this unsettling question.

Authenticity as a Core Human Value

The philosopher Charles Taylor has written extensively about the modern preoccupation with authenticity, tracing its emergence to Romantic-era philosophy and its subsequent development into a central organising value of contemporary Western culture. To be authentic, in this framework, is to be true to one's own inner nature, to express what is genuinely one's own rather than conforming to external expectations or imitating others. Creative work has become one of the primary domains for the expression and validation of authentic selfhood.

AI-generated output represents the perfect antithesis of authenticity, the ersatz in its purest form. It has no self to be true to, no inner nature to express. It produces outputs that simulate authentic expression while lacking substance entirely. For people who have invested heavily in the ideal of authenticity, whether as creators or appreciative consumers of human creativity, AI output represents a form of pollution or contamination of the cultural ecosystem.

The Disgust Response and Moral Psychology

Disgust as a Moral Emotion

Jonathan Haidt's research on moral emotions has demonstrated that disgust, originally evolved to protect us from pathogens and spoiled food, has been co-opted for social and moral purposes. We experience disgust in response to violations of purity and sanctity, to betrayals of trust, and to the degradation of things we hold sacred. The language people use to describe AI-generated output, calling it “slop,” describing it as “polluting” creative spaces, worrying about it “contaminating” search results and social media feeds, maps directly onto disgust rhetoric.

This suggests that, for many people, the objection to AI-generated output is not merely aesthetic or practical but also moral. There is a sense that something improper has occurred, that boundaries have been transgressed, that valued spaces have been defiled. Whether one agrees with this moral framing or not, understanding its presence helps explain the intensity of the reaction that AI output provokes. Aesthetic displeasure alone rarely generates the kind of passionate opposition we currently observe; moral disgust does. The ersatz is experienced not just as disappointing but as wrong.

The Problem of Deception

A substantial component of the negative response to AI output concerns deception, both explicit and implicit. When AI-generated output is presented without disclosure, consumers are actively misled about its nature. But even when the AI's origin is disclosed or obvious, there remains an implicit deception in the form itself; the output presents the surface features of human communication without the underlying human communicator.

Humans have evolved sophisticated capacities for detecting deception, which elicit strong emotional responses when triggered. The anger that people report feeling when they realise they have been engaging with AI output, even when no explicit claim of human authorship was made, reflects the activation of these deception-detection systems.

There is a sense of having been tricked, of having invested attention and perhaps emotional response in something that did not deserve it. The wartime ersatz was accepted because scarcity was understood; the AI ersatz arrives amidst abundance, making its substitution feel gratuitous rather than necessary.

Historical Parallels: Technology, Labour, and Meaning

The Luddites Reconsidered

The Luddite movement of 1811-1816 is frequently invoked in discussions of technological resistance, usually as a cautionary example of futile opposition to progress. This standard narrative fundamentally misunderstands what the Luddites were actually protesting. The original Luddites were skilled textile workers, primarily in the English Midlands, who destroyed machinery not because they feared technology per se, but because they clearly understood what that technology meant for their economic position and social status.

The introduction of wide stocking frames and shearing frames allowed less-skilled workers to produce goods that had previously required years of apprenticeship to make. The Luddites were not resisting change itself but rather a specific reorganisation of production that would destroy their livelihoods, eliminate the value of their hard-won skills, and reduce them from respected craftsmen to interchangeable machine-tenders.

Their analysis was correct; the new technologies did enable the replacement of skilled workers with cheaper labour, and the textile trades were transformed from artisanal craft to industrial production within a generation. The hand-woven cloth became ersatz in reverse, still genuine, but economically indistinguishable from the machine-made substitute.

The parallel to contemporary AI anxiety is striking. Creative workers, writers and artists, designers and programmers, have invested years in developing skills that AI systems can now approximate in seconds. The threat is not merely economic, though job displacement is undoubtedly part of the concern, but involves the devaluation of human expertise and the elimination of pathways for meaningful, skilled work. When people object to AI-generated output flooding platforms and marketplaces, they are often articulating a Luddite-style analysis of how this technology will restructure the landscape of creative labour.

Walter Benjamin and Mechanical Reproduction

The critic Walter Benjamin's 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” provides another illuminating historical framework. Benjamin argued that traditional artworks possessed an “aura,” a quality of uniqueness and authenticity deriving from their embeddedness in particular times, places, and traditions. Mechanical reproduction, photography, and film, especially, destroyed this aura by producing identical copies that could exist anywhere without connection to an original context.

Benjamin was conflicted about this change, recognising both the liberating potential of democratised access to images and the troubling implications for human-cultural object relations. Contemporary AI extends this dynamic further. Not only can existing works be endlessly reproduced, but new works can be created without any human creator. If mechanical reproduction eroded the aura of existing art, AI-generated works prompt questions about whether aura can exist for newly created works that originate from systems that lack biography, intention, or a stake in their output. In Benjamin's world, mechanical reproduction produces copies of genuine objects; AI produces originals that are themselves fake, authentic only in novelty, and empty in substance.

The Printing Press and the Scribal Response

When Gutenberg's printing press began to spread across Europe in the fifteenth century, the scribal profession faced an existential threat. For centuries, the copying of texts had been skilled labour, often performed by monks who saw their work as a form of devotion. The printing press could produce in days what had previously taken years, and it could do so more accurately and at a fraction of the cost.

The resistance to printing among established scribal communities was substantial but ultimately unsuccessful. Scribes argued that printed books lacked the spiritual quality of hand-copied texts, that mechanical reproduction degraded sacred works, and that the flood of cheap printed material would corrupt culture by making the inferior widely available. Some of these objections seem merely self-interested in retrospect. Still, other objections proved remarkably prescient: the printing press enabled the wide distribution of material authorities considered dangerous and transformed the relationship between texts and their consumers.

The scribal response to printing illuminates an essential aspect of technological resistance: objections are rarely purely technical or economic but typically involve deeper concerns about meaning, quality, and the nature of valued activities. Whether these concerns prove justified or merely transitional cannot be determined in advance. The scribes saw printed books as ersatz, lacking the spiritual investment of hand-copying. We now see hand-copied books as precious precisely because that labour is no longer necessary for mere reproduction.

Photography and the Death of Painting

When photography emerged in the nineteenth century, many predicted the death of painting. Why would anyone commission a portrait when a photograph could capture likeness more accurately and affordably? Paul Delaroche reportedly declared, “From today, painting is dead,” and the concern was widespread among visual artists.

What actually occurred was more complex. Photography eliminated certain forms of painting, particularly everyday portraiture and documentary illustration. But it also liberated artists to pursue directions that photography could not follow, thereby contributing to the emergence of Impressionism, Expressionism, and, eventually, abstract art. The artists who thrived were those who found ways to do what photography could not, rather than competing on photography's terms. Photography was not ersatz painting but something genuinely new, and painting responded by becoming more explicitly about what made it irreplaceable.

Thus, history offers a potentially optimistic template for human creativity in the age of AI, but it also reveals the costs of such transitions. The journeyman portrait painters who had made comfortable livings before photography found themselves obsolete, and no amount of artistic evolution helped them personally. Technological transitions can be creative at the civilisational level whilst being destructive at the individual level, and both aspects deserve acknowledgement.

The Information Ecology Problem

Quantity Versus Quality

Beyond psychological and historical considerations, there is a straightforward environmental problem with AI-generated output. AI systems can produce text and images at a volume no human could match, and the economics of output platforms reward quantity. The result is a flooding of information environments with material that meets minimum quality thresholds while lacking the insight, originality, or genuine value that scarcer human-produced output might offer.

This is the “slop” problem in its most concrete form, and it represents ersatz at an industrial scale. When search results, social media feeds, and output platforms become saturated with AI-generated material, the experience of using these services degrades for everyone. Users must expend more effort to find valuable output amid noise; creators find their work buried beneath artificially generated material; and platforms must invest in detection and filtering systems that impose pure friction costs. The wartime ersatz existed because genuine materials were scarce; the AI ersatz proliferates precisely because it is cheap and abundant, crowding out the genuine through sheer volume.

The Lemons Problem

The economist George Akerlof's concept of the “market for lemons” describes how information asymmetry can degrade markets. When buyers cannot distinguish high-quality goods from low-quality ones, they become unwilling to pay premium prices, which drives out high-quality sellers and further reduces average quality, creating a downward spiral. AI output creates precisely this kind of information asymmetry; if consumers cannot tell whether output was produced by a knowledgeable human or generated by an AI system, they may become unwilling to invest attention or payment in any output, degrading the market for human creators.

This dynamic helps explain why disclosure and detection have become such contested issues. Output creators have strong incentives to obscure AI involvement to maintain perceived value, while consumers increasingly demand transparency to make informed choices about where to direct their attention. The absence of reliable signals about the origin of output contributes to a general atmosphere of suspicion that affects even clearly human-produced work. When the ersatz cannot be reliably distinguished from the genuine, the genuine loses its premium.

Why This Moment Feels Different

The intensity of current reaction to AI output reflects the convergence of multiple factors that historical parallels only partially capture. AI systems have improved rapidly enough that the psychological adjustment period has been compressed, giving people less time to develop coping strategies and to adapt their expectations. The domains affected, creative expression and knowledge work, are ones where contemporary Western culture has concentrated meaning-making and identity-construction. The scale and speed of AI-enabled output generation threaten information environments on which many people depend for both professional and personal purposes.

Moreover, unlike the Luddites' frames or Benjamin's cameras, AI systems are not easily understood mechanical devices. They are black boxes that produce outputs through processes their creators do not fully comprehend, which adds a layer of alienation to interactions with them. When a photograph is taken or a text is printed, humans remain clearly in control of a comprehensible process. When an AI system generates output, something more opaque has occurred, and the human role has shifted from creator to prompter, curator, or evaluator.

The visceral response to AI output, the disgust, the anger, the sense of transgression, reflects all of these factors working in combination. The ersatz quality of AI touches something profound in human psychology: our need for authentic connection, our investment in the meaningfulness of creative work, our sensitivity to categorical violations and perceived contamination. Whether this response proves to be a transitional adjustment or the beginning of a longer cultural conflict depends on choices yet to be made, choices that will determine whether the genuine remains distinguishable, valued, and economically viable.

Some of these choices pertain to platforms and regulators, such as whether search engines and social media platforms label, filter, or deprioritise AI-generated content; whether governments mandate disclosure; and whether the information environment remains navigable or becomes hopelessly polluted.

Some belong to markets and industries, for example, whether sustainable premium tiers develop for demonstrably human work; whether new certification systems, guilds, or professional standards emerge to signal quality; whether patronage models find new forms.

Some belong to AI developers themselves, whether they build in watermarking and disclosure mechanisms or optimise for augmenting human creativity or replacing it wholesale. Some belong to consumers, whether audiences actively seek out and pay for human-created work or whether convenience and cost override concerns about authenticity once AI quality reaches a certain threshold. The technology itself does not predetermine the outcome.

Navigating the Transition

The visceral negative response to AI-generated output reflects genuine psychological and cultural concerns that deserve serious engagement rather than dismissal. For creative agencies, understanding these reactions is essential to navigating client relationships, team dynamics, and market positioning amid significant technological change.

The historical record offers both caution and hope. Technological transitions have consistently been more complex than either enthusiasts or resisters anticipated, with outcomes shaped by choices and adaptations that could not be foreseen. The Luddites were right about the immediate effects of mechanisation on their livelihoods, but wrong that machine-breaking could stop the transition. The scribes were right that printing would transform the relationship between texts and readers, but wrong that this transformation would be purely negative.

The ersatz quality of AI output, its capacity to fill the space of human creativity without possessing its essential substance, will remain a source of discomfort for as long as humans value authenticity and genuine connection. Creative agencies that approach AI with clear-eyed pragmatism, genuine ethical reflection, and strategic flexibility are best positioned to find sustainable paths through the current transition.

This requires neither uncritical embrace nor reflexive rejection, but the more complex work of understanding in depth what AI can and cannot do, what clients and audiences genuinely value, and how human creativity can continue to provide something worth paying for in an environment of increasing artificial abundance. The goal is not to eliminate the ersatz but to ensure that the genuine remains recognisable, valued, and available to those who seek it.

I am a partner in Better than Good. We help companies make sense of technology and build lasting improvements to their operations. Talk to us today: https://betterthangood.xyz/#contact